I recently came across an article about a fantastic project/art movement engaged in by West Coast artists Melanie Cervantes and Jesus Barraza (Melanie and Jesus collaborate under Dignidad Rebelde), Cesar Maxit, Ernesto Yerena, Julio Salgado and Favianna Rodriguez. The art movement utilizes the beautiful monarch butterfly to symbolize the movements of undocumented peoples across North America, which is akin to the extraordinary journey of the monarch butterfly itself.

The article, Hopeful,’Unapologetic’ Art Rebrands the Immigration Movement, encapsulates the art movement’s intentions:

“Every year, during their mating season, millions of monarch butterflies make the journey from Canada and the U.S. to a small town in Mexico called Angangueo where they coat branches and leaves like gobs of black and orange paint. Migration is built into the monarch’s DNA. For that very reason, the creature has played a central role in the rebranding of the undocumented movement. The choice in symbol is simple: Migration is natural, borders are not.” – Ingrid Rojas, ABC News

(Be sure to read the full article – there’s more art!)

While in this blog, I attempt to have a North American Native focus, historically speaking, there hasn’t been a clear boundary between North American and Mesoamerican Native peoples – if anything, it’s more of a spectrum and intermingling of experiences and even ancestry. Indigenous trade and travel across the continent is something that has existed here long before the political formations of Mexico, the United States, or Canada, and the establishment of their arbitrary borders. In fact, corn was developed in Mesoamerica, and since spread across North and South America, becoming a food staple and important part of the mythos of many Indigenous peoples. For my Ojibwe people, who are more than a thousand miles away from Mexico, our word for corn is Mandaamin, “wonder/mystery seed.” (There’s a cool story about the Corn spirit and our cultural hero Nanabozho wrestling each other – not unlike the Bible story where Jacob wrestles an angel.) Macaw feathers have also been known to have been traded up the continent, and other various Mesoamerican art, customs, and materials spread upwards as well.

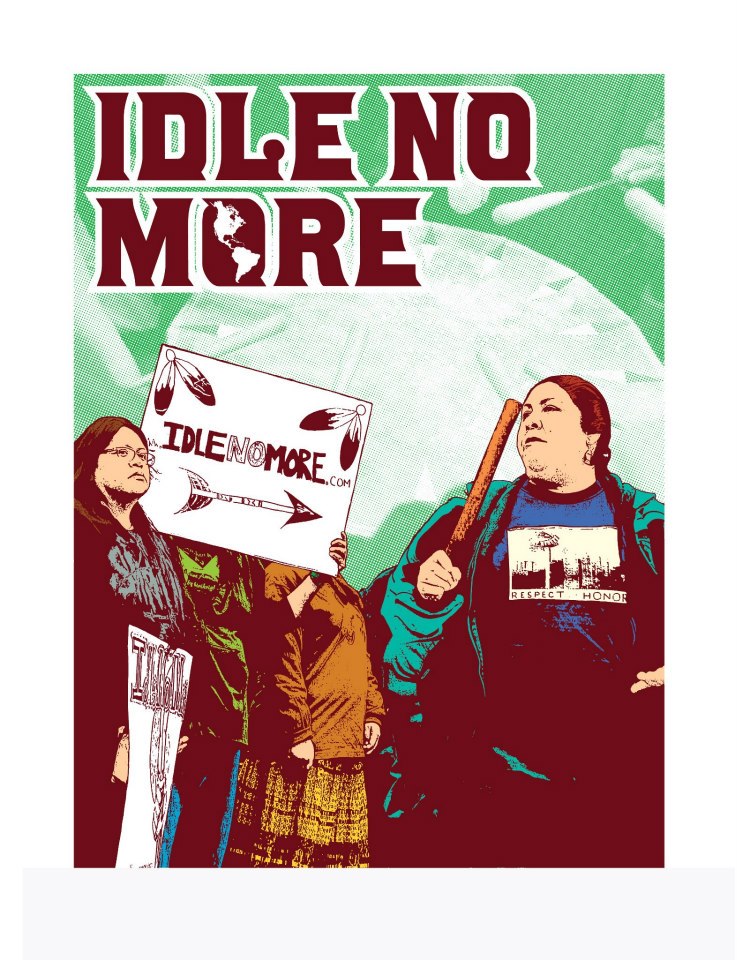

In any case, we have a lot of links, and have certainly all struggled under colonial oppression, discrimination, and reprogramming. And again, while I strive to highlight Natives with ancestry hailing from particular parts of North America, I do want to mention that Natives with Latin American or Mesoamerican backgrounds have been very active producers of artwork, posters, and other graphic design work – it’s a full subject unto itself. And of course, a number of Natives today hold mixed ancestries from both regions, as has likely long been the case.

While sneaky, dehumanizing words like “aliens” or “illegals” obscure the issue and the racial dynamics involved (even the usage of of the word “immigrant” is strange for what are largely indigenous peoples), immigration reform is truly an Indigenous issue. I am proud to say that back in 2010 at my school, I and other Natives participated in a protest against Arizona’s racist SB 1070 law and HB 2281 bill. Love and solidarity for my Native brothers and sisters!

(Also, be sure to check out Dignidad Rebelde, whose “art is grounded in Third World and indigenous movements that build people’s power to transform the conditions of fragmentation, displacement and loss of culture that result from this history.”)