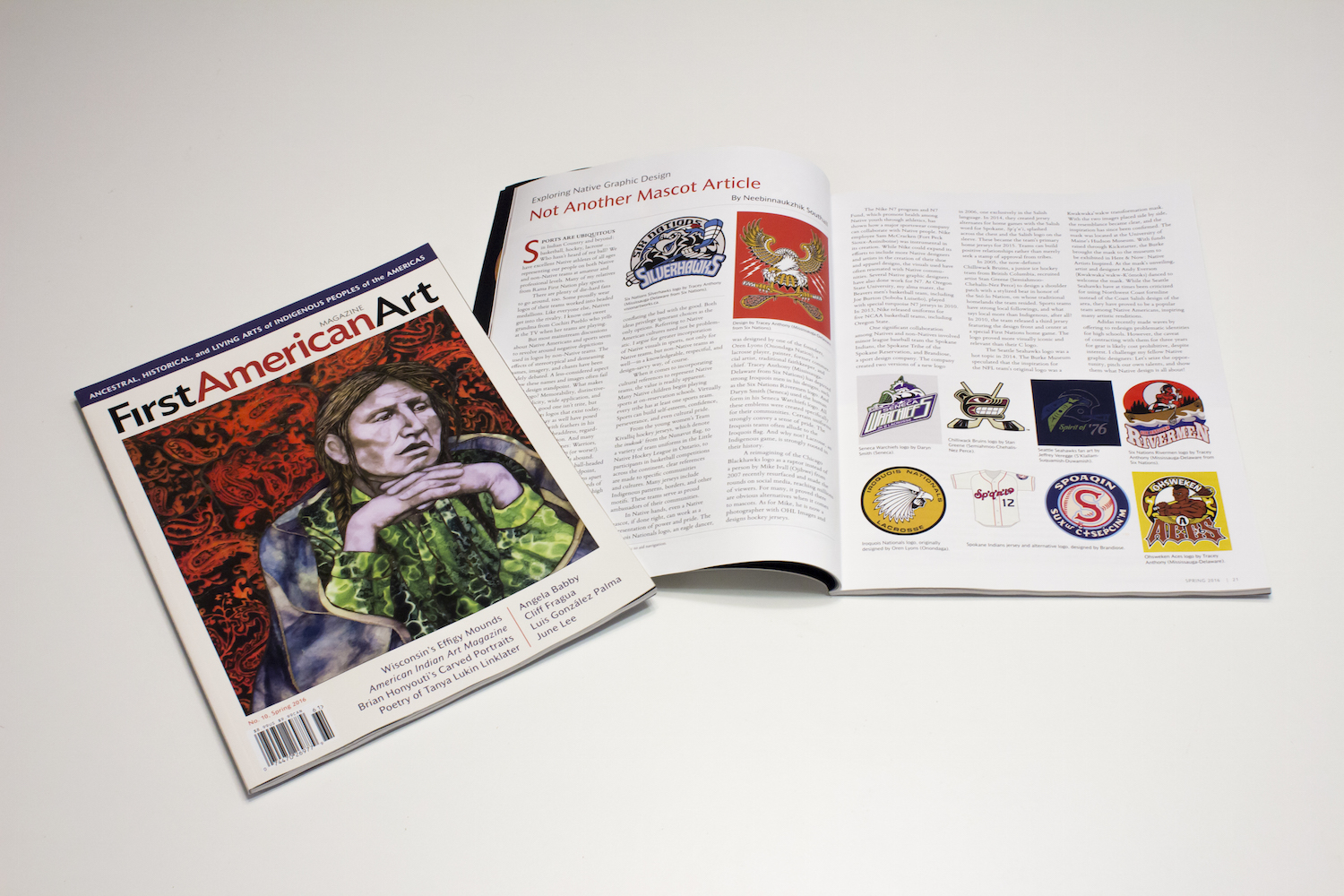

My article, Exploring Native Design: Not Another Mascot Article, which explores the intersection of Native peoples and sports in, I hope, a new way, by centering the discussion on positive design by both Native and non-Native designers. Issue no. 10, Spring 2016, of First American Art Magazine.

Not Another Mascot Article

by Neebinnaukzhik Southall

As appears in First American Art Magazine

SPORTS ARE UBIQUITOUS in Indian Country and beyond: basketball, hockey, lacrosse … Who hasn’t heard of rez ball? We have excellent Native athletes of all ages representing our people on both Native and non-Native teams at amateur and professional levels. Many of my relatives from Rama First Nation play sports.

There are plenty of die-hard fans to go around, too. Some proudly wear logos of their teams worked into beaded medallions. Like everyone else, Natives get into the rivalry. I know one sweet grandma from Cochiti Pueblo who yells at the TV when her teams are playing.

But most mainstream discussions about Native Americans and sports seem to revolve around negative depictions used in logos by non-Native teams. The effects of stereotypical and demeaning names, imagery, and chants have been widely debated. A less-considered aspect is how these names and images often fail from a design standpoint. What makes a good logo? Memorability, distinctiveness, simplicity, wide application, and relevancy. A good one isn’t trite, but for many sports logos that exist today, the same man may as well have posed

for all of them—with feathers in his braids or wearing a headdress, regardless of geographic region. And many teams have the same names: Warriors, Indians, Chiefs, and Braves (or worse!). Tomahawks and arrowheads abound. What I wouldn’t give to see a ball-headed war club! From a branding standpoint, these choices do not set these teams apart as distinctive or memorable. Hundreds of teams are guilty of this, mostly at the high school level, but even certain infamous professional teams lack unique branding. Native teams also fall into this trap.

Some conclude that all outsider references to Indigenous cultures are automatically wrong. Some refuse to acknowledge problems or make changes, conflating the bad with the good. Both ideas privilege ignorant choices as the only options. Referring to Native American cultures need not be problematic. I argue for greater incorporation of Native visuals in sports, not only for Native teams, but non-Native teams as well—in a knowledgeable, respectful, and design-savvy way, of course.

When it comes to incorporating cultural references to represent Native teams, the value is readily apparent. Many Native children begin playing sports at on-reservation schools. Virtually every tribe has at least one sports team. Sports can build self-esteem, confidence, perseverance, and even cultural pride.

From the young women’s Team Kivalliq hockey jerseys, which denote the inuksuk from the Nunavut flag, to a variety of team uniforms in the Little Native Hockey League in Ontario, to participants in basketball competitions across the continent, clear references are made to specific communities and cultures. Many jerseys include Indigenous patterns, borders, and other motifs. These teams serve as proud ambassadors of their communities.

In Native hands, even a Native mascot, if done right, can work as a representation of power and pride. The Iroquois Nationals logo, an eagle dancer, was designed by one of the founders, Oren Lyons (Onondaga Nation), a lacrosse player, painter, former commercial artist, traditional faithkeeper, and chief. Tracey Anthony (Mississauga-Delaware from Six Nations) has depicted strong Iroquois men in his designs, such as the Six Nations Rivermen logo. And Daryn Smith (Seneca) used the human form in his Seneca Warchiefs logo. All these emblems were created specifically for their communities. Certain uniforms strongly convey a sense of pride. The Iroquois teams often allude to the Iroquois flag. And why not? Lacrosse, an Indigenous game, is strongly rooted in their history.

A reimagining of the Chicago Blackhawks logo as a raptor instead of a person by Mike Ivall (Ojibwe) from 2007 recently resurfaced and made the rounds on social media, reaching millions of viewers. For many, it proved there are obvious alternatives when it comes to mascots. As for Mike, he is now a photographer with OHL Images and designs hockey jerseys.

The Nike N7 program and N7 Fund, which promote health among Native youth through athletics, has shown how a major sportswear company can collaborate with Native people. Nike employee Sam McCracken (Fort Peck Sioux-Assiniboine) was instrumental in its creation. While Nike could expand its efforts to include more Native designers and artists in the creation of their shoe and apparel designs, the visuals used have often resonated with Native communities. Several Native graphic designers have also done work for N7. At Oregon State University, my alma mater, the Beavers men’s basketball team, including Joe Burton (Soboba Luiseño), played with special turquoise N7 jerseys in 2010. In 2013, Nike released uniforms for

five NCAA basketball teams, including Oregon State.

One significant collaboration among Natives and non-Natives involved minor league baseball team the Spokane Indians, the Spokane Tribe of the Spokane Reservation, and Brandiose,

a sport design company. The company created two versions of a new logo in 2006, one exclusively in the Salish language. In 2014, they created jersey alternates for home games with the Salish word for Spokane, Sp’q’n’i, splashed across the chest and the Salish logo on the sleeve. These became the team’s primary home jerseys for 2015. Teams can build positive relationships rather than merely seek a stamp of approval from tribes.

In 2005, the now-defunct Chilliwack Bruins, a junior ice hockey team from British Columbia, recruited artist Stan Greene (Semiahmoo-Chehalis-Nez Perce) to design a shoulder patch with a stylized bear in honor of the Stó:lo Nation, on whose traditional homelands the team resided. Sports teams have strong local followings, and what says local more than Indigenous, after all? In 2010, the team released a third jersey featuring the design front and center at a special First Nations home game. The logo proved more visually iconic and relevant than their C logo.

The Seattle Seahawks logo was a hot topic in 2014. The Burke Museum speculated that the inspiration for the NFL team’s original logo was a Kwakwaka’wakw transformation mask. With the two images placed side by side, the resemblance became clear, and the inspiration has since been confirmed. The mask was located at the University of Maine’s Hudson Museum. With funds raised through Kickstarter, the Burke brought the mask to the museum to be exhibited in Here & Now: Native Artists Inspired. At the mask’s unveiling, artist and designer Andy Everson (Kwakwaka’wakw-K’ómoks) danced to welcome the mask. While the Seattle Seahawks have at times been criticized for using Northwest Coast formline instead of the Coast Salish design of the area, they have proved to be a popular team among Native Americans, inspiring many artistic renditions.

Adidas recently made waves by offering to redesign problematic identities for high schools. However, the caveat of contracting with them for three years for gear is likely cost prohibitive, despite interest. I challenge my fellow Native graphic designers: Let’s seize the opportunity, pitch our own talents, and show them what Native design is all about!